Saving the last dolphin in the Yangtze River

It was a comment simply stunning in its ignorance: in July, 2013, Wang Ding, a hydrobiology professor, was carefully explaining to a local official about the need to protect the finless porpoise of the Yangtze River. The official asked, “Is the river porpoise delicious?” Wang Ding was dumbfounded, replying, “No.” “Then why are we protecting it?” A video of this exchange was shown on CCTV, and ultimately the official’s callous gaffe—if nothing else—helped raise awareness of the importance of protecting this vulnerable fresh water cetacean. The Yangtze fin less porpoise is one of two species of freshwater dolphin living in the Yangtze River. Another Yangtze dolphin, the famous baiji, was declared functionally extinct in 2007. Compared to other species of dolphin, the fin less porpoise is small in size, doesn’t have a dorsal fin, has a stunted forehead, and a smile permanently cracks across its face. In some Chinese dialects it’s called “the river pig” (江猪子).

“Its intelligence is equal to that of a four- or five-year-old human child. It is timid, alert to any disturbances, but also vibrant and inquisitive of unknown things,” says Wang Chaoqun, keeper of fin less porpoises in the aquarium of the Institute of Hydrobiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

The Yangtze fin less porpoise’s ancestors first entered the Yangtze River about a million years ago, and the mammal lived undisturbed there until the late 1970s, when the Reform and Opening Up turned the river into a bustling “golden passage”. In just three short decades, human activity completely altered the fin less porpoise’s habitat, and the species is being pushed to extinction at an alarming rate. Every year, large numbers of the finless porpoises die due to electro-fishing, injuries caused by ships and fishing tools, water pollution, and even starvation. In 2006, the population of the fin less porpoises was 1,800; in just six years the number dropped to 1,040, a yearly decline of 13.7 percent.At this rate, the species will be extinct in 10 to 15 years.

For dolphin activist Yu Jiang, things changed so rapidly that it took him by surprise. He first became acquainted with both dolphins in 1997 in an aquarium in Wuhan, Hubei Province, which played host to the only human raised baiji in existence, Qiqi. “They also had several fi nless porpoises in the pool, but I never paid much attention to them because at that time they were still considered common in the Yangtze River,” Yu recalls. “I never thought the finless porpoise would be so endangered. We were all enchanted by the massive, graceful baiji. However, Qiqi died in 2002, and then, in 2007, a special investigation team announced their results after thoroughly searching the Yangtze River for six years; we suddenly came face to face with the fact that we had already lost the baiji. Then we learned that we would have a hard time keeping a hold on the fin less porpoises as well.” Yu remembers the day he heard the news, vividly, because coincidentally it was also the day of the one-year countdown to the Beijing Olympics, a day full of festivities and heated patriotism. The irony was not lost on him that, as a country celebrated its self-imposed international prominence, a beautiful, intelligent mammal officially died out—all part of the price paid for rapid “development”.

Yu then began work on a baiji biography, The Tragic National Treasure, but with that his attention was drawn to the baiji’s struggling cousin. He has been working on a blog project for four years, keeping a record of finless porpoise casualties nationwide. Yu is gravely concerned, as he sees similar patterns between the population decrease of the Yangtze river porpoise and that of the baiji. “In the 1990s, a cetacean expert told me that every year over 20 deaths of baiji dolphin were reported. By the end of the 1990s, baiji dolphin death reports became rare, but it didn’t mean they were better protected, just that there were fewer of them left. At present, the river porpoise is in a similar state. Every year many of them die, as a result of human activity, in the prime of their lives or even when they are very young. It’s a very ominous sign.”

Yu’s love for the finless porpoises is mingled with a sense of powerlessness, which he fi nds common among other dolphin volunteers. “It is tedious work to collect the data, but morethan that, I feel very powerless,” Yu says. “The media all over the country is on our side, but there is simply not a single [government department] who will claim responsibility for their protection. When other dolphin lovers ask me, ‘what can we do aside from forwarding your Weibo?’ I feel powerless. It’s like we want to make things happen but just don’t know how.”

The responsibility, theoretically, goes to the Agricultural Bureau. China does not have a governmental agency specifically devoted to wildlife protection; instead the role is divided between two departments: the Forestry Bureau is in charge of terrestrial animals and the Ministry of Agriculture in charge of aquatic animals. However, the administrative power of the aquatic animal protection offi ce is much less than its counterpart. This may have played a part in the government policies related to the river porpoise. The finless porpoise is currently under the government’s second tier protection, which hasn’t changed since 1988, even though their population is currently 850 fewer than that of pandas, which are under first tier protection. “It’s not the fault of the Ministry of Agriculture. The protection measures they want to carry out are hitting a wall because this will shake up the systems of fishing, shipping, water conservancy, and transportation for six provinces along

the Yangtze River,” Yu says.

Fortunately, while the government is caught in inaction, one fervent dolphin volunteer is relentless enough to put all his energy and money into saving the finless porpoises. The Yangtze Finless Porpoise Protection Association in Hunan Province is an NGO founded by Xu Yaping (徐亚平), a senior journalist at a local newspaper. The association is located at Yueyang, a city to the east of Dongting Lake.

Dongting Lake is the second largest freshwater lake in China and therefore one of the most important habitats for the finless porpoise. The vast lake, now densely dotted with fishing tools and dredgers, is no longer a haven—more of a massive trap for wildlife. The fishermen deploy means such as electrifishing and labyrinth-shaped nets that can fish indiscriminately and hyper-efficiently. When The World of Chinese called Xu, his voice was thin over the rumbling of motors and the sound of waves lapping. Xu’s team patrols Dongting Lake several times a day to stop people illegally fishing. “There are about 18,000 fishermen living off the lake. Most of them migrated here and are undereducated, living a tough life on the water. They don’t know, or care, much about how to profit from the lake sustainably,” Xu says. In 2013, a two-year-old river porpoise died in Dongting Lake with 15 large hooks in its flesh. The hooks, called gungou, are strung together and spread out on the bottom of the lake to catch large fish, but often brutally injure or kill river porpoises. Another river porpoise died in Dongting Lake without any visible wounds—possibly a result of being electrocuted, another cruel fishing technique. Patrolling the lake and confronting the fishermen can be a dangerous task with patrolmen putting their physical safety at risk. In 2012 and 2013, Xu’s colleagues were seriously injured multiple times by the local fishermen when they tried to stop the men using illegal and harmful fi shing equipment.

Sand dredging is another destructive force on the ecosystem. “Every grain of sand is like a fl eck of gold,” said Xu, in an almost mournful tone. “The sand layer is like the lake’s womb, in which the fish lay their eggs. By incessantly dredging the sand away, sometimes digging as deep as 50 meters to the bottom, the practice prevents the fi sh from breeding. Already, over 100 species of fish have disappeared from Dongting Lake, and the river porpoise suffers the most because it is at the top of the food chain.”

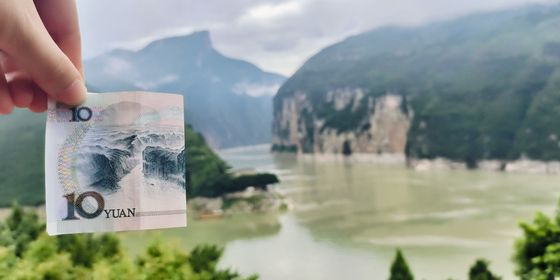

Currently there are over 50 dredges in the eastern stretch of Dongting Lake alone. Sand dredging is a highly profitable business, bringing in about 100,000 to 200,000 RMB every day. Through numerous negotiations, Xu has finally managed to stop them working at night, earning 10 hours of peace for the finless porpoises’ sonar.

Speaking of his campaigns, Xu sounds like a lonesome warrior. He and his team, of about 20 core members, have too many things on their calendar—fighting for the porpoises is a relentless task. Xu wants to relocate a large number of the fishermen, establish more finless porpoise conservation areas, win the PR war, and organize more volunteers to protect the porpoises on other sections of the Yangtze River, but all this is simply too much for one small team to take on. Under the massive workload and in a state of near-constant anxiety, Xu and his team have never had a day off.

Funds are also an issue for Xu. The association is more-or-less funded by Xu and his team members alone. He doesn’t have a foundation because, as he says, “I don’t have the time to do that.” Donations are scarce and usually come in hundreds of RMB. The biggest donation he ever received was 10,000 RMB from a woman in Guangzhou. Where there is a shortage of money, Xu uses his mianzi if he has to. With his government connections, he has “borrowed” 25 advertisements in Hunan Province from the authorities. The man is worn away by exhaustion and sometimes breaks out in fi ts of anger. “In fact, I shouldn’t be the one to do all these things. But I have no other option. The baiji already died out! Someone has to do something!”

Although frustration comes from many directions, Xu’s work has not been completely in vain. Before his association was founded, every year 30 to 40 river porpoises died in Dongting Lake. In 2013, however, only three died, and they spotted 10 baby finless porpoises in the lake. “At least I have successfully defended Dongting Lake,” he says. Idealists like Xu are hard to come by today, but it’s comforting to know that there is at least a few members of our species giving their all to save another. When asked if this course is worth it, Xu replied instantly, “It’s hopeless.” But then, after a meditative pause, he added, “but, obviously, there is always hope.”