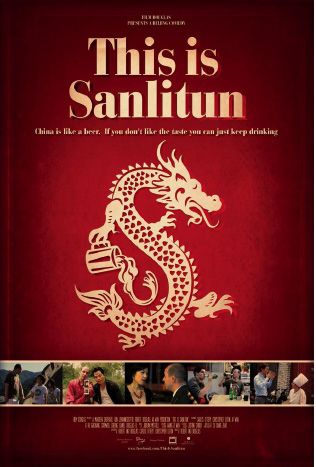

Taking a break from the bleak arena of Chinese cinema, a look at Beijing comedy, This is Sanlitun

This Is Sanlitun

This Is Sanlitun

《这是三里屯》

Zhè shì Sānlǐtún

Director

Robert I. Douglas

Writers

Robert I. Douglas, Carlos Ottery, Christopher Loton

Expat troubles are a budding new topic among directors in both the Chinese and European spheres of independent cinema. From the follies of Chinese living abroad and Americans living in China, there’s a wealth of ridiculousness to be parodied from linguistic hijinks through to any number of cultural faux pas. Such films feature expatriates searching for identity, often with mischief on their minds, or to escape heartbreak; most prevalently, these protagonists are existentially alone in their environments, uncomfortable in their own skin. It is the paradox of being a foreigner; exposure of an individual’s outward differences from the rest of the world actually causes a crisis of identity: “Who am I?” and “Why am I so different?”

Directed by Icelander Robert Ingi Douglas, and starring co-writers Beijing-based stand-up comedian Carlos Ottery and Christopher Loton, This Is Sanlitun is a rambling mock-u-mentary about the struggles of expats, which had its World Premiere at the 2013 Toronto International Film Festival.

Carlos Ottery, (also an editor here at The World of Chinese) plays British loser Gary, who makes it to Beijing, from London, in search of riches and a better life. Things don’t go as planned, and he ends up taking a variety of jobs, including becoming an English teacher while he sets about looking for his divorced wife and child. Along the way he meets Frank, an inept mentor and fellow expatriate living in Beijing who believes in all his heart that he is Chinese. It’s up to Frank and his foibles to show Gary how to live in China. The duo—one being outright assertive and plainly wrong about nearly all aspects of Chinese culture and the other being a quiet, unassuming dupe—invoke a modernized version of traditional Chinese stand-up comedy of sorts. Without one of them, the monologues might become rude or meek, but together, Frank and Gary provide a rather sobering sense of humor.

Frank: Hey mate! How much is that one?

Hēi! Gēmenr, nàge duōshao qián?

嘿!哥们儿,那个多少钱?

Bike seller: It’s 2,880.

Liǎngqiān bābǎi bāshí.

两千八百八十。

Frank: 2880? Not bad.

Liǎng qiān bā bǎi bā shí? Bú cuò.

两千八百八十?不错。

[Frank talks to Gary in English then back to the seller.]

Frank: I told him it’s 3,500. He will give you 2,880 and I will keep the rest, Ok?

Wǒ gàosu tā shì sān qiān wǔ bǎi. Tā gěi nǐ liǎng qiān bā bǎi bā shí, nǐ gěi wǒ shèngxia de, hǎo ma?

我告诉他是三千五百。他给你两千八百八十,你给我剩下的,好吗?

Frank (left) and Gary (right) high-five over an unamused Johnnie (center)

As such, This Is Sanlitun is equally uncomfortable in its realization of being a foreigner in foreign land. Sanlitun is an area of Beijing that’s known for being a major hideout for expats, replete with swarming bar streets juxtaposed against the squeaky clean mall space of The Village, full of bourgeois Gucci and Prada stores. Sanlitun is a fitting setting for the film, as there is no place in Beijing more awkwardly confused with East-West modernity than the filth and splendor of Sanlitun. The film is not only about a foreigner in a foreign country, but rather its awkward extra-diegetic perspective on just what it means to be a foreign film in a foreign country. One may not necessarily consider This Is Sanlitun to be a Chinese film, but at the same time, it’s clearly not a European film. While the foibles of Gary and Frank tend to mostly stay in English, their environment is unadulterated, modern Beijing, in all its dirt and glory. Asked whether his portrayal of Gary is at all similar to his own life, Ottery responded: “I am a foreigner in China trying to find my way, and I have taught English…So on the basic level, yes, but I’m not really like Gary. A lot of it is caricature; we saw things going on in Beijing that we found funny and exaggerated them—though not always by much—for comic effect.”

Frank: You’re Beijingers, right?

Nǐmen shì Běijīngrén, shì ba?

你们是北京人,是吧?

Old man: Oh yes.

Duì.

对。

Frank: You drink erguotou, the old Beijing liquor?

Lǎo Běijīng èrguōtóu, shì ba?

老北京二锅头,是吧?

Old man: Yes, three!

Duì, sān píngr!

对,三瓶儿!

Frank: Three bottles? Three bottles of erguotou?

Sān píngr? Sān píngr èrguōtóu?

三瓶?三瓶二锅头?

Old man: Yes.

Āi, duì le!

唉,对了!

Frank: No way!

Gànmá ya?

干嘛呀?

Old man: I will have some more in the evening.

Wǎnshang yě hē.

晚上也喝。

Frank: You’re joking?

Kāi wánxiào ba?

开玩笑吧?

Old man: No joke.

Bù kāi wánxiào

不开玩笑。

Frank: You must be pissed.

Hē de zhēnshi tài zuì le.

喝得真是太醉了。

In more ways than one, TIS will make people uncomfortable, including Beijing’s expatriates, not because it casts them as money-grubbing opportunists or Chinese fetishists (indeed both exist, though they don’t speak in such extremes), but rather because we’re not sure where the stereotypes end and begin. Between fresh-off-the-boat Gary, who knows nothing of Chinese culture at all, and Frank, who only marginally understands Chinese culture as well, there’s very little about actual Chinese culture: “You can’t lie to a Chinese person, they just see it right in your eyes,” Frank laments. In fact, the jokes are on these two foolhardy screwballs, as the Chinese people in This Is Sanlitun are portrayed with more quotidian normalcy than either foreign goof. Of course, making a film that parodies life as a foreigner in China’s capital city isn’t a wholly serious matter, and parodying confusion is always, well, confusing. “I think for people that come to China it is all a bit confusing; it certainly still is for me sometimes. And, of course, the locals are no doubt confused by a lot of the things foreigners do. I’d probably argue that China is a confused country,” says Ottery, who has lived in Beijing for nearly five years.

Ultimately, Gary’s confusion is both animated and mitigated by the developments in his relationship with his son and estranged Chinese wife, who now live in China. It’s these intimate moments between them that provide the foil to the discomforting caricatures—even weird people are still people. Gary’s son Johnnie, (Daniel Douglas-Li) who speaks half in Chinese and half in English, is arguably the most confused character in This Is Sanlitun. One can imagine how single parent families already confuse children, and Johnnie seems to be caught in the midst of two parents whose conflict represents a clash of cultural identities.

Just like almost all films that deal with expat troubles in China, This Is Sanlitun has been received by expats with mixed feelings: while some praise the movie for its portrayal of expat attitudes (despite their being caricatures), others are too bitter and retracted within their bubbles to appreciate the absurd humor about themselves.

Shortcomings aside, Beijing, according to Gary, is a place that, despite its best attempts to eat him alive, manages to remain a place with remarkable charm. Most expats seem to agree: living as a foreigner in Beijing is a day by day struggle. The question we then should ask and to which we have yet to see an answer is: “How does the other half live?”