Arise, comrades, and learn of the revolution

Social revolution and bloodshed often go hand in hand, with some revolutions redder than others. As Chairman Mao famously said: “A revolution is not a dinner party, or writing an essay, or painting a picture, or doing embroidery; it cannot be so refined, so leisurely and gentle, so temperate, kind, courteous, restrained and magnanimous. A revolution is an insurrection, an act of violence by which one class overthrows another.” The word 革命 (gémìng, revolution) has its emphasis on the character 革, which has a bloody origin.

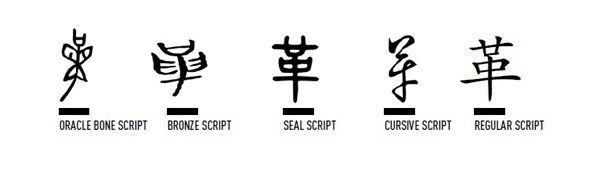

革 was actually familiar to every caveman as animal skin. Day in and day out, hunters cut their prey open and striped their pelt. The earliest form of this character (oracle script) certainly reflected that fact: a piece of spread skin with the animal’s head, limbs, horn and tails, still attached. In the idiom 马革裹尸 (mǎgéguǒshī), meaning to be wrapped in a horse hide after death, horse hide is a symbol of high honor—only for warriors who died fighting on the battlefield.

Later the form of 革 evolved with the advancement of crafts. Two strokes representing hands were added on each side of the skin (bronze script), indicating the preparation of leather. The meaning of 革 then began to incorporate such processes. The character also came to mean leather and certain leather products, such as armor or shoes. The word 兵革 (Bīnggé) literally means weapons and armor but generally refers to armaments and even war. The modern expression 西装革履 (Xīzhuāng gélǚ)) describes a smartly dressed man in a suit and leather shoes. Today, leather is 皮革 (Pígé), while synthetic leather is 人造革 (rénzàogé), or man-made leather.

A series of leather-related characters were also created with 革 as their radical. For instance, 鞋 (xié) means shoes, 靴 (xuē) means boots, 鞭 (biān) means whips, and 鞍 (ān) means saddle; the 革 radical reveals their original material.

It is quite a transformation from the tough, blood-stained animal skin to soft, smooth leather. As a result, 革 also means “to change” as in 革命 (gémìng), literally “change destiny”. The word was first used to describe the fact that one dynasty replaced another, as the destiny to rule was believed to be granted by the heavens. Later, in the late 19th century, the character was proud to be a member of the 革命党 (gémìng dǎng), or revolutionary party— as opposed to a 改良派 (gǎiliáng pài ) or reformist—which carried the hopes of a total republic. But today, when you say 革命精神 (gémìng jīngshén), or revolutionary spirit, people will assume you mean the glorious proletariat; that’s thanks to the efforts of the Central Propaganda Ministry. When you hear a 革命歌曲 (gémìng gēqǔ, revolutionary song) or a 革命故事 (gémìng gùshì, revolutionary story), think no further than the glorious red revolution. The price you pay for anti-revolution, or 反革命 (fǎngémìng), could be very high—at one point punishable by death. Luckily, there are still revolutions of other colors, such as the 工业革命 gōngyè gémìng, industrial revolution) and the 科技 革命 (kējì gémìng, revolution of science and technology).

Centering on the meaning of “change”, 革 constitutes a number of words. 改革 (gǎigé, reform) is used to describe critical systematic changes, such as 金融改革 (jīnróng gǎigé, financial reform). 变革 ( biàngé) means “transformation or change” as in 社会变革 ( shèhuì biàngé, social changes). 革 also refers to a particular kind of change—“to remove”, which was derived from the fact that the hair was shaved off of the skin during the leather preparation stage. The word 革新 (géxīn, to innovate) is short for 革 故鼎新 (gégùdǐngxīn), literally, “to remove the old and establish the new”. Similarly, 革除陋习 (géchú lòuxí) means “to remove corrupt customs or bad habits”. When a state official is fired, we use the word 革除公职 (géchú gōngzhí) or “to remove from an official post”. From animal skin to revolution, now that you know the history of 革, it’s not hard to figure out the meaning of the expression 洗心革面 (xǐxīngémiàn), literally, “to wash one’s heart and change one’s old face”. It means redemption through change.