The culture of confessing for the victims and persecutors of the Cultural Revolution

Fang Jie, a retired Human Resource Bureau director in Shanxi Province, surprised his family when he learned how to use a computer at 70 years of age—writing a 100,000 word memoir of his father, a red army official who died 30 years ago. However, the Cultural Revolution where Fang turned against his own father, insulting him in public assemblies amongst the mob, remained completely unmentioned. Similarly, Yu Guangyuan is a well-known scientist and philosopher who published nearly 100 books, including personal essays and memoirs. However, in all his prolific writings, he never once mentioned his first wife who committed suicide in 1968 at the age of 34 after two years of ruthless physical abuse and persecution.

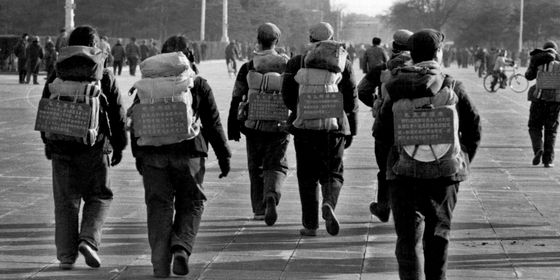

The Cultural Revolution was an unforgettable time of horror and regret for the people who participated and lived through it. Over 100 million people were involved in the movement, with nowhere safe from its brutality and no one above question. In its first month—August, 1966—1,772 people were tortured to death in Beijing by Red Guards’ bats, whips, fists, and kicks, a taste of the cruelty and terror that would rule China for the next 10 years. However, spectacularly, although almost every Chinese family has members who experienced the Cultural Revolution, it is rarely talked about even in private. Though there are not any official rules forbidding discussion of this dark time, it has become taboo for both the persecutors and the persecuted. With the exception of scar literature and a few scattered stories, the whole 10 years seem to be slipping away as China ages, lost, hushed, and forgotten. But, there are still those who—in modern day—are still willing to stand up and tell their sad tales of a country and a people in the grip of madness.

In 2008, 55-year-old linguist Wang Keming (王克明) wrote a confession of how he hit a peasant when he was young. During the Cultural Revolution Wang was forced to leave his hometown of Beijing to work on a farm in ShaanxiProvince. When the central government issued an order to carry out a new “movement”, a peasant called Gu Zhiyou was chosen as the enemy and, as such, received pidou. In a pidou, the targeted person is tried in public assembly, forced to confess their “sins” against communism and Mao, under a showering of insults, and is often physically abused while kneeling and tied up. Fortunately, in this small village, the pidou was more like a formality. After Gu received his pidou on stage, others helped him to rest and have some water. However, Wang, as a young man from Beijing where the revolution was much more cruel, was filled with anger towards the “enemy”. He continued to demand Gu confess his crimes against Mao and punched him hard in the face. In the 34 years that passed since that day, Wang has been trying to justify his actions, convincing himself that Gu must be guilty of something, but his inner turmoil continued. Finally, in 2004, he went back to Shaanxi, found Gu, and apologized. For all those years of personal torture and regret, it turned out Gu never bore a grudge. Calling Wang a “Beijing kid” like he did back then, Gu smiled and said, “It was a movement. You were only kids, what did you know?” Wang was overwhelmed by Gu’s kindness. He felt compelled to write down his experience, and published it in 2008. He wrote in the beginning of the article, “After I became middle-aged, I realized one fact: there is no such thing as an enemy.” And Wang didn’t stop at confessing his own guilt. He started a book project with several friends and sent out requests to people who had been through the Cultural Revolution, asking if they had any confessions to make. “We need to know the truth,” Wang told TWOC, speaking of his reasons for compiling his work. “We really don’t know much about the truth of the Cultural Revolution. Even though we do not know what really happened, we argue about how we should define that era. To this day, people are still arguing whether the Cultural Revolution was a good thing or not, and there still are people worshipping Mao. By confessing our guilt, we are offering our part of the historic truth.”

By 2013, through various efforts, he had 34 articles from 32 confessors. A man wrote to confess that he killed someone in a conflict between Red Guard groups. A woman confessed that her testimony caused a classmate’s suicide. Lu Xiaorong, the granddaughter of warlord Lu Zuofu, was not responsible for any persecution because of her family background; instead, she was denied higher education. However, she still felt the need to confess her “sins”, her sin of being brainwashed and not thinking independently. From Wang’s perspective, all these stories melt down to a major conflict: the conflict between political manipulation and human nature.

“I believe everyone who went through the Cultural Revolution is traumatized, whether they were persecutor or the persecuted, because we all have the same human nature. However, under some circumstances, human nature can be repressed and give way to the ‘Party nature’ (党性). When the ‘Party nature’ wind blew, hate would dominate. I felt that our generation was raised on hate. We were taught to cultivate our ‘Party nature’ since we were kids. For example, the textbooks told us to be unwavering in our political stance, take up the whip to beat your enemy, and crack down on all capitalists,” Said Wang. “Hate possessed us: wherever our eyes landed, we saw enemies. When such a generation is thrown into a turbulent age, they persecute others or become persecuted themselves—or become brainwashed. Hate was the drive for class struggle and all physical violence during the Cultural Revolution. However, when they are able to look back at history, and denounce the hate education they received, the ‘Party nature’ gives way to human nature. By confession, we are refusing to hate and seeking to love.”

“The purpose of my book,” Wang adds, “is to help people, especially young people, understand the Cultural Revolution and see the results of hate education. Nowadays there is no longer the physical abuse that happened then, but there is still intense verbal abuse out there. People are so hostile on the internet. They fight each other like gamecocks, all without any real conversation happening. People don’t seem to know that they can sit down and talk about things. I think a loss of traditional values, class struggles, and hate education all have played a part in this. No one seems to be aware there could be values other than money and hate in the world.”

The loss of values also concerns Wu Si (吴思), the editor of Yanhuang Chunqiu (《炎黄春秋》), a history magazine. In the same year, Wang Keming published his confession, Wu started a column in his magazine called “Confessions” (忏悔录).

“China used to have values higher than individual interests, such as the Confucian notions of mercy and conscience. During Mao’s era, we had other paramount values—Communist values. But, nowadays we have none. Then,who are we? We are degraded into a race that pursuesthe maximization of profits, which makes a fragile base for society. So, if a few people in this society stand up and confess, then at least it means that those people respect a value higher than profit. This value is neither mercy nor communism; it is conscience. These people give something for the whole society to respect, and they make our country look more civilized,” said Wu.

As a historian, Wu Si also sees something other than civilization in confession. “They also provide us with truths, truths that some people try to deny or ignore, but talking about these truths is how we can make sure history doesn’t repeat itself.”

However, the number of people who would stand up and speak about what they did during the Cultural Revolution is still small. In fi ve years, Wu Si only received about a dozen articles. “I would be exaggerating if I said those who are willing to admit they did the wrong thing in the revolution make up five percent of the Red Guards.” Wu said.

Zou Dongfeng (邹东锋), an editor of a Hunan newspaper, had a similar experience when he wanted to publish confessions. His newspaper has an expansive elderly readership, and Zou called for his readers to confess their wrongdoings during the Cultural Revolution in the readers’ QQ forum. He received only three letters. “Most of the people don’t understand,” he said. “Many of the people who used to be Red Guards just think they did the right thing, or they simply blame it on the era. They are not burdened by self-reflection.”

Wang Keming was in a similar situation. “Although I can’t say what we are doing has caused apathy, many people don’t understand us. Most of them say we shouldn’t be in any place to apologize because it was Mao’s fault, not ours. By confessing our guilt, we are taking the responsibility that Mao should have taken.”

Sixty-year-old Wang Youqin (王友琴) has no patience for such talk. Wang Youqin has been collecting personal accounts of the Cultural Revolution for 27 years, having interviewed over 1,000 victims, their families, and witnesses—ending in a book called Victim of the Cultural Revolution: An Investigative Account of Persecution, Imprisonment and Murder.

“These are only excuses,” she commented when asked about Wang Keming’s statement, significantly raising her tone. “Of course the Cultural Revolution was Mao’s fault. It couldn’t be more apparent. But how can one just spare themselves like that? During the Cultural Revolution nobody had much choice, and it was not all your fault if you did bad things; but, now we do have choices, and we should act like humans.”

Wang is earnest for a reason. In recent years, her name has been connected with a name that was once an idol of the Red Guards, Song Binbin (宋彬彬). They both went to the Girls’ Middle School attached to Beijing Normal University. On August 5, 1966 (a month known notoriously as “Red August” for the massive massacre that took place), their principal, Bian Zhongyun (卞仲耘), was the first teacher beaten to death by Red Guards during the Cultural Revolution, and in 1994, Wang Youqin published an account of how she died after extensive research and interviews. More importantly, she mentioned Song, as one of the Red Guard leaders, was involved. Thirteen days after the incident, Song was received by Mao Zedong himself at Tian’anmen and put a Red Guard band on Mao’s arm. Mao asked for her name, which means “polite and elegant” and said, “You should be called Yaowu (要武),” meaning “be militant”.

After that, Song Binbin changed her name to Song Yaowu and became a Red Guard idol nationwide. Soon, an article appeared in People’s Daily under the name Song Yaowu, which advocated Red Guard violence, “I’m not going to let Chairman Mao down. I’m going to be militant and brave. I pledge to carry on the Proletarian Cultural Revolution to the end…Violence is truth; it existed before and exists now, and it will still exist in the future.”

While there is not yet direct evidence of Song involved in the violence, she was an important symbol during the Cultural Revolution. Not only did she become an idol, Red Guards nationwide took a vicious turn toward violence after Mao encouraged it by giving her a new name. Before August 18 there were only two

deaths in Beijing; after that, the daily death toll quickly rose into the hundreds.

In a 2003 documentary on the Cultural Revolution, The Morning Sun, Song Binbin defended herself. “I never participated in the Red Guard destructions, not even once, but there are rumors about me everywhere…I feel so wronged, because I was always against physical violence.” She further denied that she used the name “Song Yaowu” at all, rather that it was propaganda by the government. Another Red Guard leader, Ye Weili, said in the documentary that the principal, who died with bruises and wounds all over her body, actually died of heart attack. Ironically, Song was chosen as an “outstanding alumni” at the middle school’s 90th Anniversary, and her photo was next to the photo of Bian Zhongyun.

Wang Youqin is outraged by this escapism. “The point is they don’t think they did anything wrong. They may not have necessarily killed people with their own hands, but they were a part of it; so, they have their share of responsibility. However, instead of confessing and apologizing, they attack those who tell of what happened.” For the past few years, Wang has been harassed by ex-Red Guards—both with personal attacks and hostile visits.

In stark contrast to Song Binbin and her supporters is the apology from Chen Xiaolu (陈小鲁), the son of General Chen Yi and the leader of the Xijiu (西纠),one of the most influential Red Guard organizations in Beijing. Chen wrote a letter to his middle school teachers to apologize for what he did during theCultural Revolution. He claimed responsibility for the bullying of his Red Guard group and asked forgiveness for being too cowardly to stop the many humanitarian crises of the time from happening. At the end of the letter, he wrote, “Recently there is a trend of justifying the Cultural Revolution. Personally, I think it is a point of personal freedom as to how to understand the Cultural Revolution, but under no circumstances should inhuman behavior that violates the Constitution and human rights ever happen in China again!…My apologies come only too late, but to purge my soul—for society to move forward and for the future of my country—I have to make these apologies.” While in the mainstream media he is considered as an extraordinarily courageous man, he managed to enrage some of China’s more extreme leftists. On Utopia (乌有之乡), a leftist website, many articles satirized his apology, calling him a “villain” and even demanding that Chen should apologize to Mao Zedong because Mao takes the blame for the Cultural Revolution even though the Red Guards were the real wrongdoers.

It is always hard to draw a line between the wickednessof the times and the evil of individuals, especially in the case of the Cultural Revolution, and when presented with such a grave issue, most people have chosen to keep silent and forget.

On this point, Wang Youqin loves to tell a story she heard rom a science teacher. The teacher worked on a farm during the Cultural Revolution, and he was in charge of a herd of cattle. There was a patch of thick grasses below

a big willow tree, which was a favorite food of the cattle,and, one day, the villagers slaughtered an old cow under the tree because it was too old to work; ever since then none of the cows would go anywhere near the willow tree even though the grass was delicious. The chickens, however, upon seeing the innards of their fellow hens chucked into the yard, would all hurry over and peck at the guts of their own kind.

“So mankind is somewhere between cows and chickens,”

Wang says. “But now that we have a choice, we need to

decide whether to be the cow or the chicken.”

UPDATE: Song Binbin recently made a tearful confession on Sunday regarding her part in the cultural revolution