Desertification threatens to engulf northern China

It’s a typical spring scene in Beijing; northerly winds rattle windows, dust smatters roof tops, cars, and pedestrians. Walk outside and you’re bombarded with tiny sand particles that cling to your eyes and crunch between your teeth.

For centuries in northern China, these annual sandstorms, called the Yellow Dragon, have been ripping through the city. Experience just one and you’ll know why. They roar through the city, upending construction sites and raining yellow sand on everything in their path. The largest storms can be seen from space as huge brown plumes moving from northwest China and Mongolia to blanket much of northeast Asia.

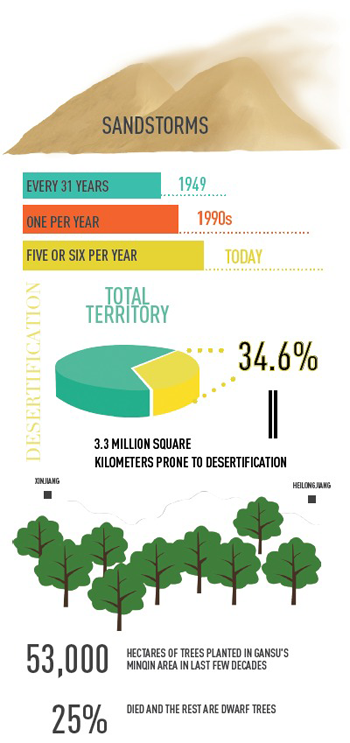

A 2005 paper in the journal Nature noted that between the fourth century and 1949, northeastern China saw a dust storm on average every 31 years. After 1990, the study reports, the average jumped to one per year. Nowadays, the average rate of dust storms for the Beijing region in northeastern China can be upwards of five or six a year.

Desertification in China is a growing problem and is the cause of the increased frequency of storms. According to a 2006 report filed by the China National Committee for the Implementation of the United Nation’s Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), the area prone to desertification in China is 3.317 million square kilometers large, accounting for 34.6 percent of total territory.

In 1978, with such an expanse of Chinese land either naturally desert or prone to desertification, the Chinese government established a formal campaign to address such threats.

Their cure-all solution? The Green Wall of China, also known as the Three-North Forest Shelterbelt Program (三北防护林体系工程 Sān běi fánghùlín tǐxì gōngchéng). It’s a 3000-mile tree belt stretching from far western Xinjiang to Heilongjiang in the northeast. According to University of Hawaii Professor of Geography Hong Jiang, the program aims to establish 35.6 million hectares of protective forests over a swath of 2,783 miles in northeast, north, and northwest China. The program is slated to take 73 years (finishing in 2050) and raise forest coverage in northern China from five to 15 percent. Others cite goals of upwards of 42 percent forest coverage.

The UNCCD reported in 2006 that the government’s intermediate objective within 10 years is to keep 20 million hectares of desertified land under control, establish 1.2 million hectares of the shelterbelt system, and enclose 11 million hectares of sandy land for forest and grassland regeneration.

Underlying such a massive long-term and nationwide program is the idea that humankind can shape and control nature, a philosophy possibly stemming from Mao-era policies. As early as 1940, Mao gave a speech at the inaugural meeting of the Natural Science Research Society of the Border Region, discussing his ideas about the relationship of man and nature. He said, “For the purpose of attaining freedom in the world of nature, man must use natural science to understand, conquer, and change nature and thus attain freedom from nature.”

China’s history of programs to “conquer nature” have hitherto included cloud seeding prior to the Olympic Games and widespread dam projects, such as the controversial Three Gorges Dam. It could be said that the Green Wall of China forms the backbone of a pervasive philosophy that humankind is more powerful than nature.

But, there are cracks in the wall.

The logistics of the Green Wall have required massive mobilization of local officials and villagers. Most of the areas impacted by the program are rural, often asking farmers or ranchers to turn their attention to re-envisioning both the local environment and their livelihoods. There are stipulations in these areas for locals to participate in a number of tree planting days each year, according to Professor Jiang.

Furthermore, the program’s widespread tree planting campaigns typically allot only one or two species of tree to an area. Professor Jiang wrote in a 2009 Epoch Times article, “In Ningxia, for example, 70 percent of the trees planted were poplar and willow. In 2000, one billion poplar trees were lost to a disease (Anoplophora), wiping out 20 years of planting efforts.” At the same time, there has been an emphasis on creating fenced-in grassland for livestock pastures, especially in areas of Inner Mongolia previously open to nomadic ethnic Mongolians.

Dead willow seedlings on the Ordos Plateau in Inner Mongolia

While the campaign sounds like a necessary one, the nuances of transforming such vast areas of habitat are much more complicated. For one, Professor Jiang notes that the project is not an anti-desertification or reforestation program as much as one of “afforestation”. Forests are not being grown in places they once proliferated, but rather in long-barren regions. Because of this, many planted forests do not survive due to the fact they don’t receive sufficient rainfall or maintain suitable soil conditions.

The use of single species as well as crowded planting complicates the survival of the forests. According to a World Resource Institute Report, of the 53,000 hectares of trees planted in Gansu’s Minqin area in the last few decades, a quarter of the seedlings have died and the rest are dwarf trees, lacking any capacity to protect the soil.

Due to the increasing inefficiencies of the program, Chinese scientists are voicing their concerns about the headstrong pursuit of the Three-North Forest Shelterbelt program.

In recent decades, the most vocal critic has been prominent ecologist Jiang Gaoming from the Chinese Academy of Sciences. “Planting trees in arid and semi-arid land violates [ecological] principles,” Jiang said to reporters of Chinese Flowers News. He called the goal of raising forest cover to 15 percent in northern China a “fairytale”.

Similarly, as early as 2003, scientists Zhang Lixiao and Song Yuqin of Beijing University’s Department of Environmental Sciences wrote a paper on the inefficiencies of the Three-North Forest Shelterbelt Program. They noted the program has not achieved its stated defensive purpose and that it must be reexamined in light of new water demands, population pressures, ecological principles, and market rules.

Despite some successful plantings, the Green Wall is failing to keep out the desert

Professor Jiang of the University of Hawaii echoes these concerns. In her research in Inner Mongolia in the early 2000s, she spoke with a local government leader who complained that despite the great effort his county made, the planting area had to be covered twice due to failing forests—and they still couldn’t make national quotas. He blamed the weather and the lazy locals.

But Professor Jiang disagrees with him. She says, “I was thinking it should be human beings cooperating with the climate, rather than the other way around.”

The larger picture of desertification in China is impacted by shrinking water tables (said to reach “dire” levels in 30 years), a lack of arable land, population growth, and record-level water and air pollution. In areas like Inner Mongolia, the expansive environmental engineering of the Green Wall has dramatically upended a traditionally nomadic lifestyle by fencing in pastures.

Dan Dong, a Ph.D. student in Geography and Geographic Information Science at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, conducted fieldwork on desertification of Inner Mongolia’s grasslands. Dong believes scientists are doing what they can to provide answers to the desertification issues, but more practical plans are needed.

“These plans should be based on scientific experiments, should be suitable to the local situation, and should reflect the opinions of community members,” Dong says.

“We need to import new ideas and thoughts, learn from successful cases, and ground the plans according to more advanced scientific technology, instead of just using old methods.”

What, therefore, is the solution to the desertification crisis? How can China’s Great Green Wall be amended to address the new and unanticipated climate concerns of the modern era?

In general, Professor Jiang believes the government is currently in the mode of merely responding to environmental crises rather than preventing them. Such large-scale and publicized events like air pollution force the government into action. Such a model, says Jiang, shows the possibilities for addressing urban industrial environmental pollution but doesn’t properly address environmental concerns in rural areas, including the overdrawing of ground water and the tremendous human effort placed on tree planting campaigns.

Despite such calls for amended action, the government’s plan is still to plant more trees, a simplistic method that, according to scientists like Jiang Gaoming and Professor Jiang, will not cure the country’s desertification problems.

Ph.D. student Dong believes part of the issue stems from a lack of education. “People must know that our environment is getting worse, and we need to protect it and improve it,” Dong says. “I think there are many people who don’t even know this, and that’s very sad.”

Professor Jiang agrees. “It works rhetorically to help urban people think the government is doing something, but ecology is a very complicated issue that requires more than one simple method that can treat all ills,” she says. “The Great Green Wall still generates a lot of positive buzz in all of China. But a lot of subtleties are not discussed. I think if they were discussed, people would be able to understand it easily. After all, it’s not rocket science.”