Paying the bills with broken bones

Zhang “The Mongolian Wolf” Tiequan is China’s most successful MMA fighter and today he spends much of his time training the country’s next generation of brawlers

Even though the air is thick with sweat and grunts, it doesn’t look like what you might imagine. The floor is a checkerboard of padded puzzle pieces—the type you might see at a kindergarten—and bottled water sits atop neatly stacked shoes. The flag of Brazil, harkening back the perceived beginnings of this sport, partners the Chinese flag on the wall. After the obligatory stretching, partners pair off; then, they square off. Sparing is rigorous, technical, and painful, often involving broken fingers, torn muscles, and not a few black eyes. The painful training is necessary, partly because bouts are imminent, but also because this is serious. This is a job.

Zhang Tiequan (张铁泉) stands with his arms crossed, watching his students with great regard. Directing and advising other coaches, Zhang slips a smile to two young jujitsu fighters as they grapple fiercely on the floor; despite being in guillotine chokes and ankle locks, they return the smile. Training is tough at China Top Team, but they all feel somewhat at home on the sweat soaked floor. As the most well-known Chinese MMA (Mixed Martial Arts, 综合格斗 zònghé gédòu) fighter on the international scene, Zhang “The Mongolian Wolf ” Tiequan hails from the autonomous region of Inner Mongolia and was the first (o f two) Chinese fighters to ever be contracted to the world-renowned UFC league. One of the founders of China Top Team—a collection of some of the finest MMA fighters in China today—he currently trains and coaches the next generation of brawlers in Beijing.

Zhang started his fighting career—as many young Inner Mongolians—practicing boke (搏克), a style of wrestling specific to Mongolia and the Inner Mongolian region. At the age of 15, Zhang began to study Greco-Roman wrestling, and, in 1999, began practicing the Chinese military-inspired fighting style o f Sanda (散打).

“The first time I saw a video of MMA, I feltincredible!” Zhang recalls, remembering when, in 2005, he was recommended for an MMA project by Chinese-American jujitsu instructor Andy Pi. Zhang was drawn by the prospect of being able to use the many skills he had learned in his varied background. “The most important reason was that, as a sportsman, I liked the sport of MMA itself, and I like to challenge myself.” Zhang says, adding: “It can also be profitable, and a good way to earn money.”

But, “The Mongolian Wolf ” is one of the few to make it. While fighting in the big Asian leagues is a dream for these MMA fighters, it doesn’t keep the lights on. Fighters on their way up have to suffer physically and financially. MMA is a relative newcomer to the international sports scene, a bedlam of fighting styles as a form of sport and entertainment. But, the game’s relative youth means there aren’t many organizations in place to recruit and support fighters, putting the financial burden on the athletes and the clubs.

Zhang Tiequan takes down Jon Tuck at a UFC event in Macao

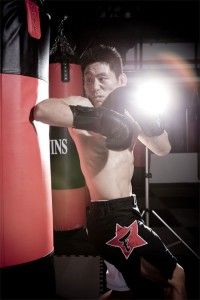

Yao Honggang (姚红刚), a recent bantamweight champion at Legend Fighting Championship, started his career in Chinese-style wresting traditional shuaijiao (摔跤). But, Yao soon saw profit in MMA, as opposed to wrestling. “MMA competition is a particularly goodplatform on the international scene; it is widely recognized around the world,” Honggang says. He and his younger brother Yao Zhiku —collectively known as Big Yao and Little Yao—were born and raised in Zhoukou, Henan Province, the sons of a PE teacher. Big Yao initially came to Beijing as a migrant worker, working as a cook, taxi driver, and doing air conditioning installations to support himself and Little Yao, who followed his older brother to Beijing to train in MMA.

Big Yao had always taken an interest in Chinese martial arts, but started to formally train in wrestling while working as a security guard for a Beijing restaurant, earning around 500 to 600 yuan per month. “In the first two years, I practiced MMA during the day, and at night would to go to the restaurant to be a security guard,” Big Yao says. “I didn’t need to pay for my training because my wrestling was pretty good. The club I joined thought I might have a promising future, so they helped me out and let me train for free. The security guard job gave

me enough money to get by.”

Unlike many of his friends and fellow MMA fighters, Big Yao managed to work his way up the road to MMA professionalism. Big Yao, also nicknamed “The Master”, commented that, while the skill and physical condition of some of his colleges may be at a higher level, most people do not have the ability to fight through the rough times and low pay connected to amateur and semi-professional MMA competition in China. “In the beginning, there is too much hardwork and practice, with only a little income. Most people find an easier way to make a living, so they change to another job.” For many young Chinese, the bright lights of Mixed Martial Arts fighting look like a good way to make money, but, for others, it’s a way out. Big Yao acknowledges that,due to his poor grades and education, university was unrealistic, putting him on a decidedly rougher road. Big Yao says: “I don’t know if I can be the world champion or not, but I won’t spare any effort. If I cannot achieve it in the end, I hope I can train my students to be able to do so.”

Success stories such as Zhang’s and Big Yao’s are hard to come by, with Chinese fighters seldom making it to a national, let alone international, standard. In Western and East Asian nations, MMA has developed into a thrilling form of entertainment, with winners taking home fame, glory, and the big bucks. However, the booming sport has struggled to find its

feet in the Middle Kingdom, and young professional and amateur fighters alike have faced many obstacles on the road towards the bright lights of MMA stardom.

Beijing-based MMA trainer, and international business manager (not to mention Ph.D. holder), Laurent Pinson, hailing from France, has been involved in the Beijing MMA scene since its infancy, first coming to the capital in 2005. “China often attempts to imitate the outside of things,” Pinson commented. “At the time, it was the fighting style in vogue, Chinese fighters tried to replicate it.”

Vale tudo in Portuguese means “anything goes”, and refers to a full contact combat event, with few rules, that gained popularity in Brazil during the 20th century. “It didn’t matter that vale tudo should only be for professionals,” Pinson reflected almost affectionately on the fledgling fights of some of Beijing’s initial MMA matches: “Its one 30-minute round, with head butts, elbows, knees….it didn’t make sense!” After competing himself in these early, chaotic I matches, Pinson and a friend decided to get a bit more serious and opened MMA Beijing, a martial arts training club based in Haidian District, Beijing. While Pinson is competent in teaching MMA in Mandarin, the overwhelming majority of his students and trainees are foreigners.

In the eyes Chinese viewers, Pinson mentions: “As soon as you go to the floor, it is considered very violent, because this looks like a real fight.

Big Yao, born Yao Honggang and today known as “The Master”, practices his reverse elbow. Before he was a successful brawler, he worked security at a restaurant.

It becomes a dajia (打架), or a brawl, rather than a civilized competition.” In Pinson’s experience, when Chinese audiences see the close-quarters grappling and submission techniques common to MMA and unfamiliar as they are with the technique and training of the sport, they often laugh.

However, a break from the traditional aspects of kung fu may be the firestarter this sport needs in for the new generation. Cui Yihui, a 22-year-old student on his summer holiday back to Beijing from studying economics in Chicago, is one of China Top Team’s eager youths who see the real-world value of a sport such as MMA, as opposed to traditional Chinese martial arts. “Personally speaking, kung fu is just like a show; you need to make it look good.” Tie commented that, while MMA doesn’t necessarily look good, it is much more intensive and practical. “Take a look at my appearance!” He beams, sweat dripping off his brow after an intense training session in Brazilian jujitsu. “As you can see, MMA is much more real.” The short, action-packed rounds in MMA may also appeal to a new generation of young people who are accustomed to instant gratification and jammed-packed entertainment.

While agreeing that support for MMA will have to start from the youth in China, trainer and gym manager Simon Shieh sees that encouragement for young people in amateur competition is where the sport will get its foundation. Shieh is the product of the supportive amateur league communities, often found outside of China, for combat sports. After moving to China in 2006, Shieh studied Sanda for two years, moved to learning Muay Thai, and later training in Zhang Tiequan’s China Top Team at the age of 19. At just 21 years of age, Shieh now manages one of the Black Tiger gyms in Beijing and was part of the team that helped coach Zhang in his second UFC match in 2011: Zhang vs Darren Elkins, in Huston, Texas, USA.

Pinson remarks that the concept of amateurship in Chinas MMA sphere doesn’t really exist; it’s all about the professional: “There are two divided systems.” Within the semi-professional system the quality of competition is fairly low and the standards in the professional system are substantially higher. “Even if you have people who have the sprit, the quest, the dream,” Pinson says, “if they don’t compete with each other [through amateur leagues], then the level of the professionals will never be extraordinary.”

Champions rarely come through the amateur system in China, as there is little financial or moral support for those who seek to make it big. Shieh also observed that the MMA league systems themselves can be somewhat difficult to navigate for an amateur fighter, as MMA doesn’t have the “visible ladder” seen in more conventional sports like football or tennis.

Most up-and-coming MMA fighters, like Big Yao, are required to self-fund their studies, and simultaneously work and train, just to make ends meet. With this setback, Pinson laments that—by the time a fighter has found a way to support their dedication to MMA—it’s often too late.

Despite the obstacles, Cui commented on the improvement of youth support for MMA in recent years, “It’s getting better and better,” he says. “Now you can see many teenagers studying MMA. They use it to relax or get healthy, and it pays off.”

“The Mongolian Wolf ” also sees the future of MMA in China’s youth: “Once young people pay more and more attention to MMA, the sport will become popular in China.” Zhang’s investment in the next generation of MMA fighters is clear, and his dedication to his club is undeniable.

Zhang Tiequan spars with Legend Fighting Championship welterweight champion Li Jingliang

Zhang hopes that, through his guidance, MMA will provide a future for these young athletes. “Concerning the future, I mainly want to be responsible for my club, and I want to expand our club. There are currently 16 people following me who want to go down the path of MMA. These fighters have a passion for MMA and train themselves conscientiously.”

At 24, Liu Jiajia, or Alison, is one of the few females following the MMA path, and embodies Zhang’s faith, seeing him as a mentor: “We have great respect for Zhang Tiequan,” Alisonsays. “He has been leading us.” It’s clear that Alison (a student, fighter and worker at China Top Team) looks at Zhang as her MMA guru, one of the benefits o f being a pioneer in the field. “The club earns almost nothing, but those of us who are passionate about MMA have the same goal; we help each other to go on.”

One day, Alison hopes to make it to a professional level and make MMA her job, not just a hobby. “I am not sure what kind of results I can achieve, but I want to see how far I can go on this road. I hope I can reach the top.” She coyly smiles as she says, “This is my dream.”

While a lot of significance is placed on reaching the professional level, Alison says it’s not all about winning: “Becoming a champion is of course very important, but it is not all just

to take the title. In each match, there are winners and losers, and through this competition, you can continue to improve.”

“On the way,” Alison reflects on the journey to MMA stardom, “some people will give up half way. I think a person who can persist to the end, regardless of the outcome, is the real winner.”

In China, there are currently only two commercial MMA promoters in town; Ranik Ultimate Fighting Federation (appropriately known as RUFF and based out of Shanghai) and Legend Fighting Championship (Legend) from Hong Kong. RUFF, founded by Canadian businessmen Joel Resnick and Saul Rajsky, is the only MMA organization to be sanctioned by the General Administration of Sports of China and is the largest exclusively Chinese MMA promotion. Zhang feels strongly that commercial and media support, rather than government support, will be the driving force for Chinese MMA in the future. “I believe that, with more media attention, MMA will increase in audience ratings and a lot of people will start to like the sport.”

Regardless of how long it takes for mainstream support of MMA to kick off in China, the encouragement of the existing MMA community will ensure that those who have the passion will find their way to the guts and glory of MMA fame, whether it’s in the domestic or international arena.

Young athletes like Alison know they’re fighting an uphill battle, but hope is still very much alive: “But we continue to go on, relying on the dream [of reaching the big-time]”. Thankfully, young and up-and-coming fighters like Alison and Big Yao are not alone on the MMA road, and they have the experience of veteran fighters like Zhang to help guide them. “If it is just one person, it’s really hard to go on,” Alison says, “but we can continue to move forward if we do it together.”

UPDATE 8/7/2013- TJ: UFC officials recently announced that they will begin holding tryouts next month for ‘The Ultimate Fighter: China’. Featherweight, lightweight and welterweight fighters wishing to participate in the latest version of the reality show can tryout on : July 21st at Beijing’s Metropark Lido Hotel, July 25st at Marina Bay Sands Singapore, and August 3rd at the Venetian Macao.

Chinese You Need

Mixed Martial Arts – zònghé gédòu, 综合格斗

wrestling – shuāijiǎo, 摔角

submission – tóuxiáng, 投降

professional – zhuānyè de, 专业的

He lost by submission.

Yīnwèi tā “pāi de” tóuxiáng, suǒyǐ tā shūle.

因为他 “拍地” 投降,所以他输了。

She is a professional athlete.

Tā shì yī wèi zhuānyè de yùndòngyuán.

她是一位专业的运动员。

![truecrime-podcast-covewr]](https://cdn.theworldofchinese.com/media/images/truecrime-podcast-covewr.format-jpeg.width-325.jpg)