An inside look at our writers’ search for Sidney Shapiro, a legendary literary translator who has lived in Beijing for more than 60 years

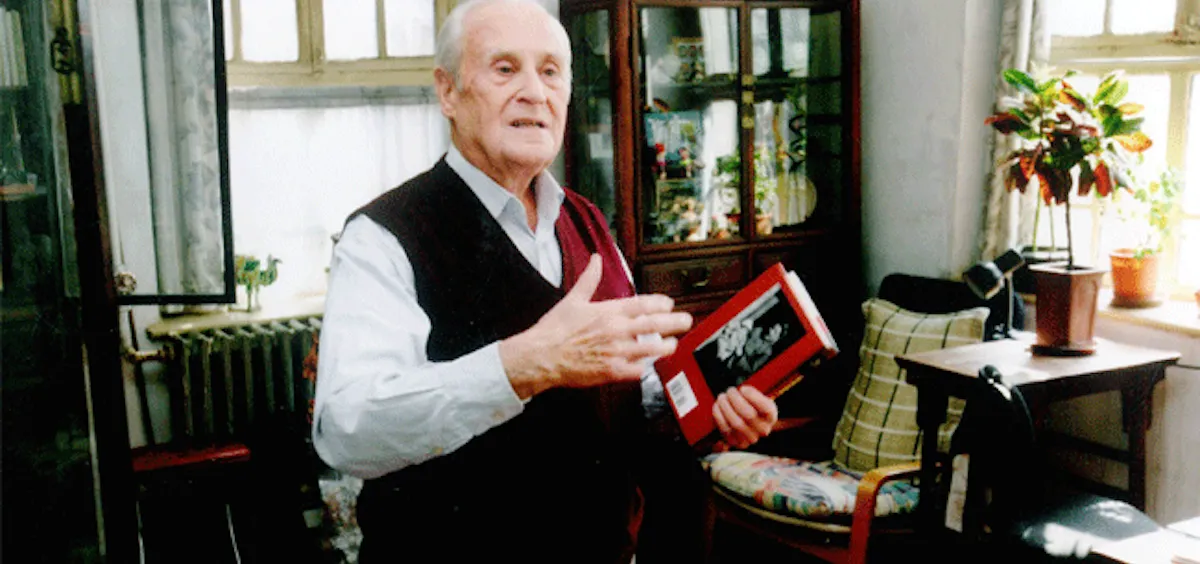

In our November-December “Literature Issue,” we include a feature about Sidney Shapiro, the preeminent literary translator who’s been living and working in China for over 60 years. Shapiro has lived a fascinating life and is even more of a character in person. In the accompanying blog series about Shapiro, I describe my experience getting in touch with the translator, and going to his house to interview him.

Shapiro first appeared on our radar thanks to our coworker Andy, a veritable storehouse of cultural trivia.

“Allegedly,” Andy said, spreading his hands wide over our conference table, “there is this American translator who lives in Beijing…”

“Yes,” we said.

“One of the most important translators of his generation…”

“Yeah…”

“Who is 96 years old, has lived here since the 40s and is allegedly still living here in a Beijing hutong.”

(Pause for stunned silence.)

To understand our reaction, it’s important to realize that, among most Westerners, it’s generally considered impressive if you’ve lived in China more than five years. Ten years is a great achievement, and 20 is almost unheard of. Shapiro has lived in Beijing for more than 60.

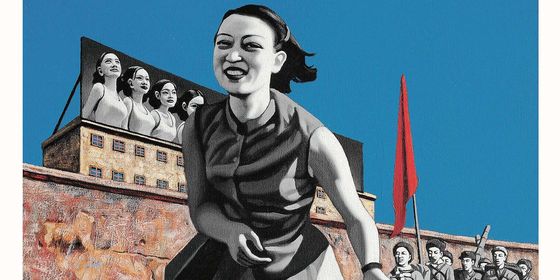

As such, he materialized in our minds as a kind of mythical creature, the unicorn of expats who’s seen something that only a handful of Westerners have: China during the most turbulent years of the 20th century, through liberation and the Cultural Revolution all the way to its current state as a rising world power

Our goal in hunting Shapiro down, then, was twofold: of course, we wanted to know about his literary career, about his translations and his thoughts about the changing face of Chinese literature. But just as important was the raw curiosity about his life, the desire to hear stories from the trenches from an ex-American who witnessed a period of history that, for many Westerners, remains shrouded in mystery.

And so we started hunting. After a week or two of fruitless searching, I had, in desperation, hatched a plan to go down to Houhai, the area where Shapiro lives, and just start asking around for nage hen lao de laowai (the really old foreigner). There can’t be that many old white people living in that neighborhood, I figured. And then, the day before I was set to go, one of my coworkers dropped a piece of paper with a phone number on my desk. “Sha Boli,” she said, using Shapiro’s Chinese name.

“Really?” I said. I seized the slip and held it up to the light like I was examining a fake bill.

“Really,” she said. “It came from a friend at Foreign Language Press.”

For a second I was overjoyed; and, a second later, filled with dread. In the two weeks that I’d been searching for Shapiro, I’d also been reading articles about him and talking to journalists who’d interviewed him. One told me, “He demands that journalists read his autobiography before doing an interview. Otherwise he’ll just yell at you and turn you away.” Another writer, who’d interviewed Shapiro recently and painted him as grumpy and confrontational, sent me Shapiro’s contact info along with the sentence, “Don’t mention my name.”

I let Shapiro’s phone number sit on my desk for two days, using the excuse that I wanted to finish reading his autobiography before I called him. “You don’t have forever,” my editor warned me. “He’s 96, for God’s sake. He could go at any time.” So it was with trepidation that I finally dialed Shapiro’s number, and waited for him to pick up.

“Wei!” an old man’s voice shouted into the phone.

Caught off guard, I paused for a second. Somewhere in the back of my mind, I hadn’t quite accepted the idea that Sidney Shapiro was a real person. A 96-year-old, New York Jew-turned-Chinese cultural icon was just a bit too fantastical for my mind to absorb. And yet here he was, in all of his century-old, Brooklyn-accented glory.

“Ah hi, is this Sidney Shapiro?”

“Yes, yes,” he said, sounding impatient. “And who is this?”

Stumbling a bit over my words, I told him that I was from The World of Chinese magazine, and that we were interested in writing an article about him for our upcoming literature issue. Would he be interested in letting us come interview him?

Shapiro began to soften as he realized what I was calling him for. Far from curmudgeonly, he turned out to be friendly and gregarious, interspersing our conversation with self-deprecating chuckles and asking me questions about myself.

He was not, however, gung ho on doing another interview.

“Since I won that—what’s it called—that Charm Award, it seems like I have journalists coming to my house every day,” he told me. “And it’s always the same questions—why did you come to China, why did you stay… and I’m just so tired of it!” I had no idea what the Charm Award was, but I pushed ahead bravely.

“We could do something different,” I said, hopefully. “I’ve read your book and a number of your interviews…”

“Yes, my book! Have you read it?” he asked.

“I’m finishing it now,” I said.

“Well, it’s all in there,” he said. “Everything you need to know. And there’s a lot of stuff about me on the Google. You can find it all on the internet these days.”

“But I’d love to focus more on your career, you know—ask some questions that aren’t covered in the other interviews…”

“I’m very busy these days,” Shapiro said. “I have many engagements…”

We went back and forth like this for some time, with me cajoling, Shapiro deflecting. But in the end, Shapiro’s sense of responsibility won out: “Well I suppose it’s my job to do these kinds of things—interviews and such,” he said.

We arranged an interview tentatively for the following week. Shapiro told me to call him the day before to nail down the time.

But when I called Shapiro the following week, he’d changed his tune. His voice was sharper, more impatient. He told me he’d need a formal introduction to our magazine, telling me again and again, “If I don’t have it, I simply can’t receive you, dear!” This time, he seemed more cautious, and asked questions that I would have expected the first time around.

“How long do you think this will take?” he asked.

“Um… two or three hours?” I said.

“Two or three hours!” he shouted.

“Too long or too short?”

“Too long, of course too long!” he exclaimed.

After promising I’d scale back the time, send him a formal introduction and bring him some American-style goodies (bagels with lox and an apple pie), Shapiro relented. We could come by, he said, the following Tuesday at 1 p.m. sharp.

Back in the office, we crunched plans with our photographer like members of a SWAT team going in for a sting.

“Now this guy is old, so we gotta be in and out!” our designer told Tyler, the photog. “There won’t be time for lots of poses and setting stuff up, so you gotta be ready. I’m talkin’ actions shots while they’re interviewing. And you have to be prepared for the light…”

Meanwhile, our managing editor pored over my questions while I tried to speed-read through the final 200 pages of the biography. We only had a couple days to prepare, and there was still a lot to do—not the least of which was figure out where in Beijing I could buy bagels and lox.

After a few bounced emails led to another another tortured phone conversation, Shapiro wrote to say that he had finally received my introduction to the magazine and would be willing to “receive” me. He sent directions to his house and said if we got stuck, to just ask someone for directions. “Ask anybody for Sha Boli. I’m quite well known around here.” And then, in bold: “Looking forward to seeing you on Tuesday — and putting your pie to the ultimate test!”

Read on with part two.